Sometimes, the sky just isn’t big enough.

One of the earliest reported aircraft bird strikes was in 1908. Orville Wright was the pilot. 1912 recorded the first fatality as a result of a bird striking an airplane, and the problem has grown exponentially over the years. More than 490 people have perished as a result of birds striking their airplane. The most famous bird strike in history occurred in 2009, when Captain “Sully” Sullenberger’s Airbus A320 suffered multiple bird strikes, crippling the aircraft and causing the Captain to make a dead-stick landing in the Hudson River. Captain Sullenberger had encountered a flock of Canada Geese, and his 90-ton aircraft proved to be no match for the flock of 10-pound geese. Captain Sullenberger was superbly trained and prepared for this situation and skillfully maneuvered his powerless airplane to a safe landing in the river. In the years since he has remained a strong and vocal advocate of preparedness training.

In 2022, more than 17,000 bird strikes were reported in the United States. That works out to about 50 per day, and the figure is fairly consistent throughout the world. Airports in migratory paths, such as Denver International, or near bodies of water are subjected to even higher numbers. Since 1995, Denver International Airport (DIA) has reported more than 9,000 bird strikes. Right behind DIA is Dallas-Ft. Worth Airport (DFW) with more than 7300 bird strikes within a similar timeframe. You may check your airport’s bird strike history Here.

Where Bird Meets Airplane

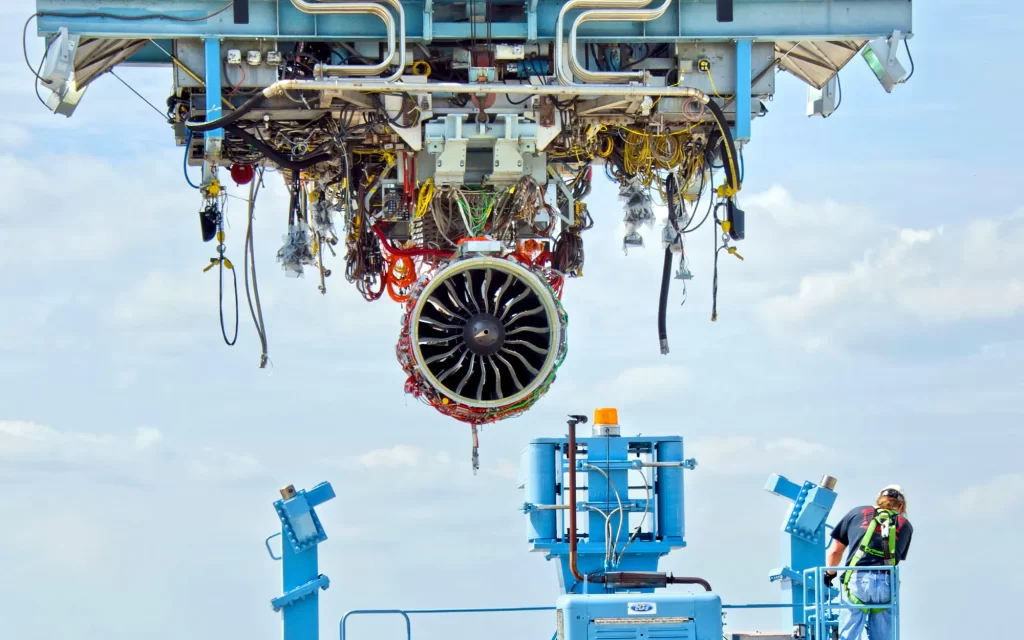

A bird strike may occur anywhere on the airplane – the wings, windshield, radome, tail, and, most importantly, the engine are all susceptible. Captain Sullenberger’s aircraft ingested geese into both engines, immediately destroying the engines – and the geese. The Federal Aviation Administration requires aircraft manufacturers to test their aircraft, especially the engines, to withstand certain levels of bird strikes.

“The procedure is simple. First the engineers firmly mount the enormous engine on an outdoor test stand. Then they gradually open the throttle, urging it to maximum climbing speed where it bellows like a wounded Kraken and blows like an uncorked hurricane. The giant fan blades spin faster and faster until their tips are moving at close to the speed of sound, and the engine’s bowels are hot enough to melt steel. And then, into the mouth of this Brobdingnagian blender furnace, this magnificent technological jewel, the engineers hold their breath, cross their fingers, and launch an unplucked four-pound chicken.

The ‘chicken test,’ as it is widely known (although any four-pound bird will do), is but one of a series of bird ingestion tests any new engine must pass before the FAA certifies it. Along with the single four-pound bird (recently raised to eight pounds for very large engines), the engine must also swallow a volley of eight one-and-a-half pound birds, fired in quick succession, and a further volley of sixteen smaller birds of three ounces each. If the turbine disintegrates or catches fire when the chick hits the fan, if the ‘pilot’ cannot shut it down afterward, or if it releases blade fragments through the engine housing, then the engine fails the test and slinks off back to the drawing board. The tests with smaller birds are more demanding: engines also fail these tests if their output is reduced by more than twenty-five percent, or if they fail within five minutes.”

Sullenberger was lucky in one regard – his bird strike occurred during daylight hours. Nearly 25% of all bird strikes happen during nighttime which amps up the risk factor considerably. Most bird strikes happen during the takeoff or landing phase of the flight as there are more birds closer to the ground. Birds have been encountered, however, as high as 40,000′ above sea level.

Airports are taking significant actions to lower the incidence of bird strikes. One such action is to control the habitat by removing food sources, standing water, and vegetation and keeping grass short so birds can’t nest or shelter. Other initiatives include:

- Visual deterrents – Using bird netting, scarecrows, or airport spikes to keep birds away from runways, hangars, and radar equipment

- Auditory deterrents – Using bird-repelling sound systems, noise generators, predator calls, or lasers to startle birds or disrupt their habitat

- Using trained wildlife management personnel to disperse birds or employing falconry to reduce the bird population

- Radar systems – using avian radar systems to track bird flocks and their movement and density.

Air Cannon at Airport

Dogs are used near airports to discourage birds

Research Continues

The Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., studies the remains of more than 11,000 birds a year involved in aircraft bird strikes. These remains, always mutilated, are identified and classified by species in an effort to learn more about the circumstances that bring birds and airplanes into conflict. This work plays a crucial role in air safety. Identifying specific species—such as European starlings, sometimes called “feathered bullets” because their dense bodies make them more damaging—helps aircraft makers design engines, fuselages, and windshields that can better withstand collisions. It also lets them know how their current designs are holding up in the skies.

Progress is being made.

Over the last three decades, the Federal Aviation Administration has recorded every reported midair encounter between bird and plane—roughly 285,000—in the National Wildlife Strike Database. Somewhat amazingly, just 651 bird species have ever been involved. Knowing the specific types of birds that are in their skies helps airports keep them from the flight paths of jumbo jets.

Take New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, which in the late 1980s was having problems with a population of nearby laughing gulls colliding with departing planes. Federal wildlife experts armed with shotguns were tasked with firing on the gulls. In 1990, there were 136 recorded incidents involving them. A year later, that number dropped to 60. Today, there are fewer than seven gull strikes a year at JFK.

What can you do?

You should trust the initiatives of the FAA, your local airport, and the research organizations mentioned above. Understanding the problem and being aware of what measures your airport uses can put your mind at ease. Knowing that airline pilots are keenly alert to bird strikes and are trained in what to do when one occurs will make your next decision to travel by air easier.

Welcome to 3-Minutes A Day University, where every day you can learn a little about a lot of things in three minutes or less. We help you expand your knowledge and understanding of the real world, and 3-MAD University is tuition-free. Our wide-ranging syllabus includes a fascinating insight into topics including Health and Medicine, Science, Sports, Geography, History, Culinary Arts, Finance and the Economy, Music and Entertainment, and dozens more. You will impress yourself, your friends, and your family with how easy it is to learn facts and perspectives about the world around you. One topic you will never find covered is politics. We hope you enjoyed the previous three minutes. If you liked this post, please pass it along to a friend.

Was this email forwarded to you? Subscribe Here.

© Copyright 2024. 3-Minutes A Day University All Rights Reserved. Unsubscribe